Write the text of your article here!

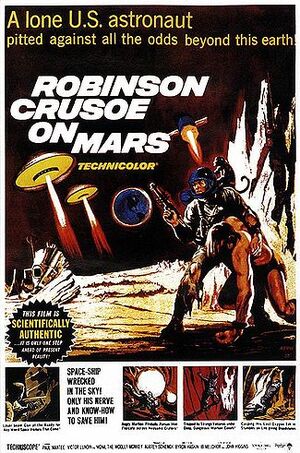

Robinson Crusoe on Mars is a 1964 Techniscope science fiction film retelling of the classic novel by Daniel Defoe. It was directed by Byron Haskin, produced by Aubrey Schenck and starred Paul Mantee, Victor Lundin and Adam West. It was released on DVD for the first time as a special edition from The Criterion Collection on September 18, 2007.

Plot[]

Commander Christopher 'Kit' Draper (Paul Mantee) and Colonel Dan McReady (Adam West) are the crew of Mars Gravity Probe 1. When they reach the planet, they are forced to use up their fuel to avoid an imminent collision with a meteor. With the ship now stuck in orbit, they have no choice but to eject to the surface, the first men on Mars. McReady is killed in the landing. Draper is stranded, with only a monkey named Mona for company.

He finds a cave for shelter. Then, he figures out how to obtain the rest of what he needs to survive. First, he burns some coal-like rocks for warmth and accidentally discovers that heating them gives off oxygen. This allows him to refill his air tank and move around in the thin atmosphere. Draper then constructs a crude sand clock that sounds an alarm to awaken him for a needed dose of oxygen. Later, Draper notices that Mona keeps disappearing periodically and that she is uninterested in the dwindling supply of food and water. He gives her a salty biscuit, but no water; when Mona gets very thirsty, he lets her out and follows her to the underground pond she has found. As a bonus, there are also edible plant "sausages" growing in the water.

As the days grow into months, Draper slowly begins to crack from the prolonged isolation. He watches helplessly as his ship, an inaccessible "supermarket", periodically crosses the sky. Without fuel, the ship does nothing when he orders it by radio to land.

One day, while walking about with Mona, Draper notices a rock standing in an unnatural position, as if deliberately planted as a marker. He looks at the ground around it and sees bones. He brushes away at the soil to expose the skeletal remains of a hand in a black bracelet. He digs up the rest of the skeleton and determines that the creature was murdered, as the skull is charred. Frightened, he signals his ship to self destruct to remove all signs of his presence.

Just in time as it turns out, as Draper sees a ship descend and land just over the horizon. At first, he believes it to be a rescue ship from Earth. In the morning, he heads towards the landing site, only to see an advanced alien craft in the sky. Realizing his error, he approaches cautiously and sees slave labor being used for mining. One of the slaves (Victor Lundin) escapes, running into Draper. The alien ships blast the area as the two flee. The stranger has black bracelets on his wrists just like the one Draper found earlier. That night, they witness the aliens blast the mine area and depart. When they investigate, they find the dead bodies of the other slaves.

Draper names his new acquaintance Friday, after the character in Robinson Crusoe, and starts teaching him English. In return, Friday shows him "air pills" that provide oxygen. They gradually grow to trust and like each other.

After a while, the aliens return, tracking Friday by his bracelets. The aliens blast the castaways' hiding place, forcing Draper, Friday and Mona to flee through the underground Martian canals. They eventually end up at the polar icecap. Exhausted, freezing and nearly out of air pills, they build a snow shelter "just like the Eskimos." Draper finally succeeds in cutting Friday's bracelets off. A meteor crashes into the ice cap, creating a firestorm and melting the snow.

Just then, they track an approaching spaceship. At first, Draper believes it to be the enemy again, but then their radio broadcasts a human voice. Draper identifies himself, and a lander comes down to pick up Draper and his companions. The credits then roll as Mars recedes in the background.

Production[]

Many of the Mars scenes were filmed in Death Valley National Park, California, at Zabriskie Point, Ubehebe Crater, and the Devil's Golf Course.

The alien mining ships are very similar in design to the Martian war machines in the 1953 version of The War of the Worlds. It is unclear whether they were recycled props or new models. Byron Haskin also directed the earlier film.

These ships are often confused with the aliens' space craft, but this is incorrect. Draper sees a single ship land and depart. The ships that repeatedly blast away at the planet's surface are apparently the aliens' version of mining equipment.

Interestingly,Ib Melchior's original Robinson Crusoe on Mars screenplay,the alien Friday was from a planet called Yargor,in the Alpha Centuri star system.Much of Friday's Yargorian dialogue was fully scripted in his native tongue.For the feature film,however,Friday's home solar system was changed to Alnilam (the center star in the belt of the constellation of Orion),and actor Victor Lundin altered the lines to a dialect mirroring Mayan phrases and terminology. Presented here is Ib Melchior's dictionary of those unused Yargorian words,which was included in his illustrated screenplay.This is the exsact dictionary presented in Robinson Crusoe on Mars DVD booklit.A great glimpse into the creative process from Criterion jacket designer Eric Skillman. In his latest entry he talks us through the creation of the cover artwork for the 1964 cult sci-fi Robinson Crusoe on Mars (starring Batman's Adam West).

[Art is by the wonderful Bill Sienkiewicz]

That second [illustration] was exactly what we were looking for. Draper's hunched over posture really gives the sense of struggle against overwhelming odds, and how can you not love Mona in the foreground? Since the jagged peak in the center was going to be pretty much obliterated by the branding and spine title treatment anyway, we figured we may as well lose it, and since Mona was already in her space suit, no need to keep Draper in his helmet. So we gave Bill the go-ahead to start painting the final illustration. Meanwhile, I decided to tweak the type a little bit, and eventually wound up here, which captured just a little bit more of the period look we were aiming for.

Breif Yargorian Dictionary

- Yargor- Friday's home world,Alpha Centuri star system.

- Tzrahamashtz-Friday's Native name.

- Yarg-Native of Friday's home world.

- Ven-No.

- Rash varnot-Don't move.

- Iro-I.

- Nardat-Freind.

- Ordunat-Enemy.

- Eraf-Danger.

- Ahtu-You

- Tzah-Look.

- Vorsa-Hurry.

- Dardaro-Guards.

- Veerke tzagnit-Writing equiptment.

- Lidah-The sun (sol)

- Lidahnom-Solar System.

- Lidahsil-Earth (sol III)

- Lidahra-Mars(sol IV)

- Meshtah-Careful.

- Liatmas tzagnit-Communications equiptment.

- Crawga-Understand.

- Igar-Yes.

- Roblan-Far away.

- Ashani-Family.

- Shanim-Woman(wife).

- Yargorian numbers

- Lusa-Zero.

- Ne-One.

- Goh-Two.

- Sil-Three.

- Ra-Four.

- Tahn-Five.

- Sor-Six.

- Sorne-Seven(Six One).

- Sorgah-Eight(Six Two).

- Sorsil-Nine.(Six Three).

- Sorra-Ten.(Six Four).

The Review[]

Every month when I check out the new movies being released on DVD from companies like Image, Anchor Bay, and the raft of foreign companies that cough up obscure horror flicks in those ridiculous Region 2 Pal formats that prevent most of us fans in the U.S. from ever seeing them (though the "real" fanboys and gals can find a way to see anything they want, right?), I marvel that even the cruddiest Ted V. Mikels film can get the attention that you would expect to see lavished on a Brando movie (earlier rather than later, I'm not talking about The Freshman or The Score here). But you know, I try so hard to control my temper. Jean and the kids at the Freedom School tell me that I can't resolve all the world's problems by watching half-assed bootleg copies of sci-fi films. But then I see a movie like Robinson Crusoe on Mars and I see this beautiful little film and I think about how it's going to have to carry around the burden of knowing that a movie like Zombie has been released on DVD about six different times already and it just makes me want to go CRAZY (scene of MonsterHunter's big smelly bare foot kicking the chief of Paramount Pictures upside his bald head). My Billy Jack flashback having ended, I can tell you that the point remains that what you have with RCOM is that rarest of birds: an intelligently done survival tale (aside from the dubious science) with the absurdly spectacular drive-in title. Whereas a movie like Invasion Of The Saucer-Men lives up (or down depending on your orientation) to its title, this one is like that movie that Tom Hanks made about being a castaway or something. I don't recall the title, but he was cast away from civilization onto some fancy island and by doing a bunch of stupid stuff he ended up dating a volleyball. Oh, the movie was okay since I only paid like two bucks to rent it, but really, was there anything in the contract I signed at my video store that said I had to stare at Tom Hanks' skanky chest for in excess of two hours? I suppose that was simply part of my own survival tale. I know some of you snobs out there are still a bit reticent to believe that RCOM could be better than any thing Hankie could ever do. The only thing you need to know is that while Hanks co-stars with a piece of sporting equipment (and not even a cup, for crying out loud!), the dude who's trying to survive in RCOM is helped by his little monkey pal, Mona.

One of the amazing things about this movie is that it's so enjoyable and only stars three people (and a monkey) and one of those people is Adam West. Adam plays Colonel Dan McReady, the dude in charge of this two-man/one-monkey mission to Mars. Right away, this movie distinguishes itself from the bulk of these outer space adventures when you see that instead of their ship being this really big room with tables of pseudo-scientific gizmos (levers, dials, and blinking buttons are tres-futuristic!) it's this cramped little space where both guys have to be in separate compartments and communicate via a video screen. There's no goofy old professor smoking a pipe wondering if something strange awaits them the surface, there's no sex-ay homemaker/woman astronaut that does the typing and fixes the dinner, and I don't remember anyone lighting up a cancer-stick on board neither. Adam plays it remarkably straight as well causing me to breath a sigh of relief (I had feared that along with the monkey, they would have packed a bunch of ham on board as well).

At this point in time it looks like Col. Dan is going to be our main character, but you know how those dang runaway meteors can play havoc with the command structure as well as the plot. Before you know it, Col. Dan has to make some kind of fancy u-turn with the ship and has to expend all the fuel getting themselves into some kind of orbit where the won't get pulled down into Mars by the planet's gravity. Col. Dan and his partner, Commander Draper, eject in separate escape pods where they are promptly pulled down into Mars by the planet's gravity. Draper makes what we in the astro biz call a "hard landing" and somehow survives the impact to crawl out and try to get a sense of what he's got himself into. First he finds out that he can't breathe the air on Mars for too long before he needs a dose of good old American oxygen. Kind of would of been nice to figure all that out before lifting up your helmet visor and taking a big whiff of Martian stink, but I guess if we knew all this we wouldn't need to be tromping around down there anyway (when Batman wrecked their ship, they were on their way home - wouldn't the make-up of the atmosphere be one of the measurements that they would have taken?). Draper goes off to find a little shelter and take stock of his situation.

Once inside this cave, Draper goes about the business of surviving in the inhospitable conditions. He figures there's enough oxygen to last about sixty hours, water to last about 2 weeks, and it will be four to six weeks before Sports Illustrated gets his subscription changed over to the new address. He knows that he needs to figure out a heat source to survive the cold nights and the oxygen problem before he deals with anything else. He also needs to go and find Adam West (Have you tried your local shopping mall?). Draper walks over the desolate landscape (the movie makes good use of its Death Valley locations) and soon comes upon the wreckage of Col. Dan's escape pod. Draper looks around and sees Col. Dan's arm outstretched from beneath the wreckage, a really sweet class ring on one of the fingers. Draper calls out to him (I'm sure Col. Dan is just taking a nap there in the dirt underneath the twisted metal (keeps him out of the sun you know - good for one's complexion) and Draper peeks into a hole ripped in the wreckage and makes that "eww, Col. Dan's landing was a lot harder than mine" face and I'm thinking that you don't want to forget that dope ring. That might be just the thing to trade a dumb Martian or Orion Miner or something like a spaceship with warp drive so you can get home. It's just like when Andrew Jackson bought Manhattan from the Indians with some money that had with his own face on it! Well, he takes the ring and then he spots a furry tail sticking up from behind a rock. Concerned that the Martians in these parts have monkey tails that are no doubt tipped with a fast-acting toxin that is poisonous to intrepid American astro tough guys, he points his way futuristic revolver at it (as good as the film is, the astronauts are armed like taking a space trip was like going to the old west or Gary, Indiana. Before he can bust a cap in Mona's ass, she shows herself and Draper is jacked that he is going to be having monkey stew tonight!Still,it's good Colonel Dan McReady was killed,since if he survived,good old Adam West would be doing the Battusee or would that be the Marstiantusee in their Marsian shelter and Commander Draper would really be considering killing him,in favor of keeping Mona around instead of him.One wonders,did Batman frack up the landing of his ship or did Mona sabotage,so he could survive and not Adam West.Actually, Draper takes Mona back to his cave and prepares to die since he never found any oxygen to replenish his tanks. He tells Mona to go ahead and eat all the rations she wants so that she at least could die on a full stomach and then he lays down next to the fire (he found some strange rocks that he got to burn) and passes out, the oxygen finally exhausted.This ofcourse,would make very short movie and a pretty crappy ending,so the writers cheat a bit here,despite all claiming the story could factual.

Draper wakes up and realizes that the rocks have given off oxygen as they burned. He theorizes that the rocks must be a strange rock where oxygen is trapped inside of them (that's why they could burn in the first place). I theorized that Commander Draper was one lucky dude. Oxygen problem solved, Draper starts fretting about the lack of water he has (This is a guy who's always going to worry about something, no matter how good he has it - first oxygen, then water - what's next? Food?). Even as he rations water, he notices that Mona never seems too thirsty. Combine that with the fact that Mona runs off all day to some secret locale and Draper has the makings of a plan so crazy it just might work. It goes something like this: follow Mona to her secret watering hole. He tracks her as she runs off into the rocky desert and the next thing you know Commander Draper is falling through a hole in the ground and landing in a heap at Mona's secret watering hole. I love it when a plan comes together. Course it probably would have been easier if he gone in the way Mona went, but the important thing is that the fall didn't bust him up too badly. While there, Draper also discovers some seaweed sausages or something that is almost as good to eat as the paste he had been eating out of the toothpaste tubes. You know if I was an astronaut and they were going to make me eat those cruddy paste meals, I would refuse to go anywhere until they developed a grilled cheese flavored one. Man do I love grilled cheeses!

Later Draper is wandering around and finds the grave of a humanoid creature. He runs back to the cave he calls home and takes down his American flag, pulls up the welcome mat, then blows up his ship that orbits above via remote control so that no one will know he's there. Then he sees a ship flying around and follows it. This ship is blasting rocks with laser beams and before you know it a big tan guy with a Sonny Bono haircut is lumbering around trying to not get his big tan ass blowed off. Draper has the dude come and stay with him. Eventually he calls this guy Friday (interestingly, Draper never refers to himself as Robinson Crusoe, but does compare himself to Christopher Columbus, probably because he was in the wilderness by himself so long that he couldn't wait to ride the Nina, if you know what I mean!). Friday is an escaped slave of these other humanoids who are from another planet and just on Mars mining some ore. I'm not real sure how Draper got all that from Friday's grunting and hand gestures that all looked like the same sweeping motion to me, but I guess they probably train for this situation down at Cape Kennedy when they're in space camp.

It turns out that these mining dudes really want their slave back and they keep returning in their ships to blast the ground and harass Draper and Friday. This was the part of the movie that didn't make a lot of sense to me. If he was just a slave, why bother trying to get him back? The point that he was expendable is really driven home when Draper and Friday happen onto a mining site where all his people that were enslaved and brought to Mars with him had been killed by the miners. What's the point of wasting all those resources (several spaceships scouring Mars) to kill one dude?Maybe Friday owes them alot of money or maybe these Orion Rednecks just got so pissed off,that common sense and thevprofit mergin lost to one slave getting away.Or maybe it's ok,if they kill the slave,but let get away and that different-a blow to their superior egoes.Southerns in the South,would mistreat their slave on the plantations,but let get away and becomes hunt them down at all cost,just they got pissed off.Anyway it keeps them on the move though and they end up at the polar ice cap and are freezing to death and then things heat up and the movie ends with a pretty easy wrap-up considering how realistic they had concentrated on making things in the rest of the movie (well, as realistic as you can be when you have Adam West piloting your most advanced spaceship and you end up living on Mars with a monkey as your roommate).The movie ends with Commander Draper and Friday receiving a signal,from those Orion Slavers.but an Earth ship.Obviously,the inferior technology of Earth scared off those Redneck Orion Slavers real fast,because suddenly just like,they are gone from the film,without any explaination,other Friday loses finally those Orion Slave Handcuffs,once Commander Draper finally cuffs them off with some wire.

An excellent film all the way around, it constantly surprises you with its efforts to keep things authentic, with Draper concentrating on locating the basic needs to survive instead of battling fearsome looking monsters and leering at buxom space honeys (though that sounds like a good movie as well). Paul Mantee plays Commander Draper with the right mix of resolve and desperation. Determined to stay alive, he improvises, tries to stay focused, but also can't help but have moments of disillusionment. Mantee never lapses into drama queen territory here though he could have (see Heston in Planet of the Apes) and raged and whined against the unfairness of it all. Draper says that he was trained for two months in an isolation chamber but that was different because he knew he would be coming out of it. Now he believes he's never going to see anyone again. He even starts to fall asleep standing up and thinking that his pal Col. Dan is back from the dead. The hopelessness of it all would overwhelm the best of us after awhile and it may have done so with Draper, but for Friday's fortuitous appearance. Where Draper saves Friday from the immediate threat from above, Friday likewise saves Draper from a solitary existence, something that would eventually have killed him just as surely as a laser blast from above (maybe worse - to be driven mad, but left alive to wander Mars by yourself). The use of the Death Valley locations and the infrequent use of bad special effects make us believe that he is on another world and that his survival is anything but assured. In a movie like this, you're always waiting for the other shoe to drop, when is that really stupid part going to happen? This time it doesn't and if you want to quibble with the tacked on happy ending that's your business, but I think after everything Draper went through, he deserves it. Mona, too.

Reviews © 2004 MonsterHunter

Cast[]

- Paul Mantee as Commander Christopher Draper

- Victor Lundin as Friday

- Adam West as Colonel Dan McReady. West would later become famous as the star of the television series Batman.

- Barney, the Woolly Monkey as Mona the monkey

Songs[]

Two songs were inspired by and named after the movie. One was sung by Johnny Cymbal, the other by Victor Lundin. Lundin wrote the song "Robinson Crusoe on Mars" to perform during his highly popular science fiction convention appearances. It became so beloved by fans that he recorded it for his 2000 album Little Owl. A music video for Lundin's song was created by the Criterion Collection in 2007 for the DVD release of the film.[2][3]

Notes[]

Template:No footnotes

- ↑ DVD]][[The Criterion Collection

- ↑ "Robinson Crusoe on Mars Music Video" on Youtube

- ↑ "Music Video" (supplementary material made for DVD release). Robinson Crusoe on Mars. DVD. Criterion Collection, 2007.

18Sep07

Robinson Crusoe on Mars: Life on Mars By Michael Lennick[]

In my dreams, Mars keeps changing: gone are the verdant Barsoomian fields explored by John Carter and Princess Dejah Thoris in Edgar Rice Burroughs’s novels; the arid, canal-laced deserts that witnessed the final exodus of H. G. Wells’s desperate invaders; the mythical cities and false Ohio farmlands of Ray Bradbury’s The Martian Chronicles. As of this writing, the ancient Red Planet of our cultural dreams and nightmares has been under nearly fifty years of assault by science, reason, and an escalating armada of robotic emissaries, yet it manages to keep bouncing back, more enthralling than ever. As science-fiction author Larry Niven once put it (in an introduction to some tales set within his own constantly changing Martian landscape): “If the space probes keep redesigning our planets, what can we do but write new stories?”

So it was quite surprising to view the 1964 film Robinson Crusoe on Mars for the first time in decades and find that it scores most highly for its verisimilitude. Given the scarcity of information then available, the filmmakers did a remarkable job of representing some of the conditions on our nearest planetary neighbor, nearly a year before the first close-up views of the real Martian surface were beamed back by the NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory probe Mariner 4.

Screenwriter Ib Melchior had already made a career of shifting comfortably between nuts-and-bolts reality-based SF (Men into Space, The Outer Limits) and more fanciful monsterfests like Journey to the Seventh Planet and The Angry Red Planet, his directorial debut (another entertaining Martian expedition, this one chock-full of ultranasty, astronaut-devouring beasties). In preparing his heavily illustrated first-draft screenplay for Robinson Crusoe on Mars, a film he intended to direct, Melchior was clearly seeking a middle ground: native plant and critter life galore, but this time in support of a lonely astronaut’s internal struggle.

Conflicting projects forced Melchior to drop out of Robinson Crusoe on Mars, leading to a very different take on the material once director Byron “War of the Worlds” Haskin signed on. When Melchior wrote his original screenplay, the canal-strewn visions of nineteenth--century astronomer Percival Lowell were starting to wane but still had power. (I remember our science teacher advising us that if there weren’t any surviving Martians, we’d just have to make do with the plant life and lower animal forms he and our textbooks were sure still inhabited the planet.) Lowell’s ancient, dying Martian engineers inspired the first rocket pioneers, including Robert Goddard and Wernher von Braun, while giving rise to such early science-fiction literature as Wells’s cautionary metaphor The War of the Worlds. In subsequent novels, television series, and especially movies, the planet took the blame for any number of terrifying attacks on small-town America, from the deeply disturbing visions (at least to this eight-year-old) of William Cameron Menzies’ Invaders from Mars all the way to a rather unfortunate 1964 cinematic attempt to kidnap Santa Claus, in order to amuse a young, green-hued Pia Zadora. (All right, it was called Santa Claus Conquers the Martians—though if you had to ask, you probably didn’t need to know.)

By this time, a new reality was starting to emerge. Stanley Kubrick and Arthur C. Clarke had begun work on 2001: A Space Odyssey, while the world was caught up in a superpower competition, launched by a brash young president, to land on the moon by decade’s end—a farsighted, twenty-first-century dream that, at least in the minds of most science-fiction fans, would kick-start our inevitable egress to the planets and beyond. It was against this background that director Haskin and company began scouting Death Valley, California, for Martian locations, one week to the day after President Kennedy’s funeral. Borrowing heavily from the designs, nomenclature, and jargon of NASA’s upcoming Project Gemini two-man orbital training missions, the filmmakers set out to explore the challenge of surviving in an alien landscape, as realized high in the Death Valley mountains that had towered over so many westerns filmed in the valleys below. In an age that saw Daniel Defoe’s original survival tale, as well as the accomplishments of the space race, played as high camp (Gilligan’s Island, I Dream of Jeannie, It’s About Time), Haskin was setting out to create the adventure for real.

Haskin had directed some of the genre’s most memorable epics in the fifties and early sixties (The War of the Worlds, Conquest of Space, and several classic Outer Limits episodes, including “Architects of Fear,” “The Sixth Finger,” and Harlan Ellison’s “Demon with a Glass Hand”), but his career stretched back to the silent era (during which he worked as a cinematographer for D. W. Griffith) and included several years at Warner Brothers in the thirties and forties, as head of visual effects, an arcane field he helped invent. That F/X background served Haskin well on Robinson Crusoe on Mars, where he employed the clear skies over Death Valley as a natural blue screen, replacing the dazzling azure dome with a situation-specific variety of red and pastel skies that would look eerily familiar to anyone scanning the alien landscapes beamed back by the Viking landers a dozen years later. Indeed, Haskin’s prophetic choice to portray Mars as a dead planet that keeps unveiling new surprises continues to resonate as our increasingly sophisticated robotic explorers transmit their streams of data and wondrous images back home.

Production values notwithstanding, what makes Robinson Crusoe on Mars hold up, when most SF films of its day don’t, is the central compelling story, already 250 years old when Melchior began his adaptation. Once the basic problems of survival and shelter have been solved, Defoe’s classic eighteenth-century tale reveals itself to be about isolation and loneliness, and it’s in those quiet moments that Robinson Crusoe on Mars truly comes alive. Adam West’s typically muggy acting in the film’s opening scenes is far surpassed by his truly creepy and surreal materialization before our hallucinating hero late in the movie, while Victor Lundin provides a lovely, nuanced take on Defoe’s Friday, now reconceived as an escaped intergalactic mining slave. But it’s actor Paul Mantee, as Commander “Kit” Draper, who does most of the heavy lifting. Mantee (who bears a striking resemblance to Mercury astronaut Alan Shepard, America’s first man in space) has said that he believes the film’s challenges sometimes overwhelmed him at this early stage of his career, but he managed to strike a deft balance between the lightness and humor of his relationships—human, alien, and simian—in the first and third acts of the film and his steely will to survive even the intractable sentence of solitary confinement that the middle act imposes. Mantee has spoken at length of how tough these scenes were on him—endless days spent trying to convey Draper’s incremental triumphs and tragedies, without anyone else on set to play off of, a unique acting challenge made only slightly easier by his growing friendship with the animal actor hired to play his sole pre-Friday companion. (I recall wondering at the time why Mona the Woolly Monkey was credited only as “The Woolly Monkey,” but Mantee has cleared up the mystery: it turns out Mona was actually played by a talented young newcomer named Barney. I’d always felt sorry for the poor little critter, struggling with that incredibly uncomfortable-looking spacesuit and -helmet, although Mantee has revealed Barney’s far nastier wardrobe accessory—the fur-covered diaper he was strapped into every morning to enable him to more accurately portray the winsome Mona. Clearly no Method thespian he.)

Robinson Crusoe on Mars carries a heavy burden of contradictions and debatable ideas, apparent even to us impressionable kids way back when. One could discern a fairly strong religious subtext running through the film; indeed, both disaster and a near rhythmic series of salvations—heat, shelter, breathable air, food, and companionship—seem to pop into Draper’s life at just the right moments. Still, the real driving force of this movie is the thoughtfulness of the director, screenwriters, designers, et al. Despite some notorious poster art, Draper is no ray gun–toting space adventurer (though he does pull out a nasty-looking revolver on a couple of occasions. Why were so many early movie astronauts packing heat?). In fact, Draper’s tools and technology are some of the most impressive elements in the film, despite the occasional cognitive dissonance (e.g., such futuristic, yet still somehow retro, NASA technology as the Mars Gravity Probe orbital vehicle’s ultrarealistic functions being driven by a mechanical computer that looks more like one of Vannevar Bush’s late-1920s differential analyzers). More impressive is the remarkably prescient portable VTR-and-camera combo that plays such a crucial role in the film, looking very much like the black-and-white Portapack units Sony would unleash on the aching backs of news cameramen and fledgling filmmakers (myself included) in the late sixties.

Even the film’s most questionable choices came about through serious reflection—though by the third act, compelling moments are sitting cheek by jowl with misfires. The alien miners (certainly one of the sillier aspects of the movie—and I’m not just referring to Friday’s faux-Egyptian sandals and hairdo) are introduced via Draper’s clandestine Portapack videotaping of the mining operation—all deeply spooky, until we get way too long a look at one of the alien slavers, decked out in a leftover Destination Moon space suit. (Even at that, darkening the faceplates might have prevented us from seeing the clearly non-emotive extras within.) Probably the film’s biggest controversy—and ultimately one of its most intriguing visual elements—came in the form of the aliens’ ray-blasting mining vessels. The decision to step-print the ships’ motion (eliminating every other frame, to double the crafts’ apparent speed) created an eccentric, jerky movement that was meant to correspond to UFO reports of the era, but really just looked weird, freakish—and yet was oddly memorable. A larger problem lay in the design of the alien craft. Haskin seems to have instructed veteran designer Al Nozaki to create near duplicates of the Martian war machines he’d built for Haskin’s The War of the Worlds. Humans are pattern-recognizing creatures, and I recall this from childhood as one of those major “willing suspension” disconnects, for it was assumed the filmmakers had taken the cheap route and just repainted one of the beautiful copper miniatures from the earlier film. I’m not sure if it’s heartening or even more discouraging to learn that was not the case, that in fact three brand-new miniatures, based largely on the earlier design, were created for Robinson Crusoe on Mars. Thinking back, the irony of former Martian invaders violently invading Mars was somewhat thin compensation for my fellow SF geeks as we emerged from that particular matinee.

And yet for all its flaws, Robinson Crusoe on Mars remains exciting, moving, and relevant—particularly now, as we begin to make concrete plans to send humans to Mars within the next few decades. The Red Planet of our cultural dreams may have constricted somewhat under the recent deluge of photographic and robotically gathered evidence, but such tantalizing new realities make us more enthusiastic than ever to explore firsthand those windswept dunes, rock-strewn plains, and burgeoning river valleys, under rich, salmon-hued skies. In the end, perhaps all is indeed prophecy. As both Ray Bradbury and Carl Sagan suggested in their very different musings, ultimately, the Martians will be us.

- New, restored high-definition digital transfer

- Audio commentary featuring screenwriter Ib Melchior, actors Paul Mantee and Victor Lundin, production designer Al Nozaki, Oscar-winning special effects designer and Robinson Crusoe on Mars historian Robert Skotak, and excerpts from a 1979 audio interview with director Byron Haskin

- Destination: Mars, a new video featurette by Michael Lennick detailing the science behind Robinson Crusoe on Mars

- Excerpts from Melchior’s original screenplay

- New music video for Victor Lundin’s song “Robinson Crusoe on Mars”

- Stills gallery of behind-the-scenes photos, production designs, and promotional material

- Theatrical trailer

- PLUS: A booklet featuring a new essay by filmmaker and space historian Michael Lennick, Melchior’s “Brief Yargorian Dictionary” of original alien dialect, and a list of facts about Mars from his original screenplay

See also[]

- List of American films of 1964

External links[]

- Template:Imdb title

- Template:Amg movie

- Template:Rotten-tomatoes

- The Criterion Collection Website Entry

- Paul Mantee interview

- Review of the movie

- Article about the movie

- Review and Information on the Restored Version of the Film

ru:Робинзон Крузо на Марсе